Vayema’en –

There’s a famous musical trope in this parsha on one word: “vayema’en” — and Yosef refused.

That song hints that this wasn’t a casual no. It wasn’t instinctive. It was an inner struggle.

A few weeks ago, when we spoke about Eliezer, we noticed that major life decisions often involve a three-way consideration: values, identity, and worldview. Yosef faces that same three-way struggle here.

First, Yosef could have said: I’m a slave. I own nothing—not even my own body.

But he immediately answers himself: My master trusts me. Betraying that trust would destroy everything.

Second, he could have said: I’m young, handsome, alone, far from my family. No one will ever know.

But then another voice speaks: My family’s name. My morals. My identity. That’s what’s really on the line.

Third, he could have said: I’m completely alone in a foreign land.

But he knows he isn’t alone. Hashem sees everything.

That’s not just temptation.

That’s identity under pressure.

So how does Yosef win?

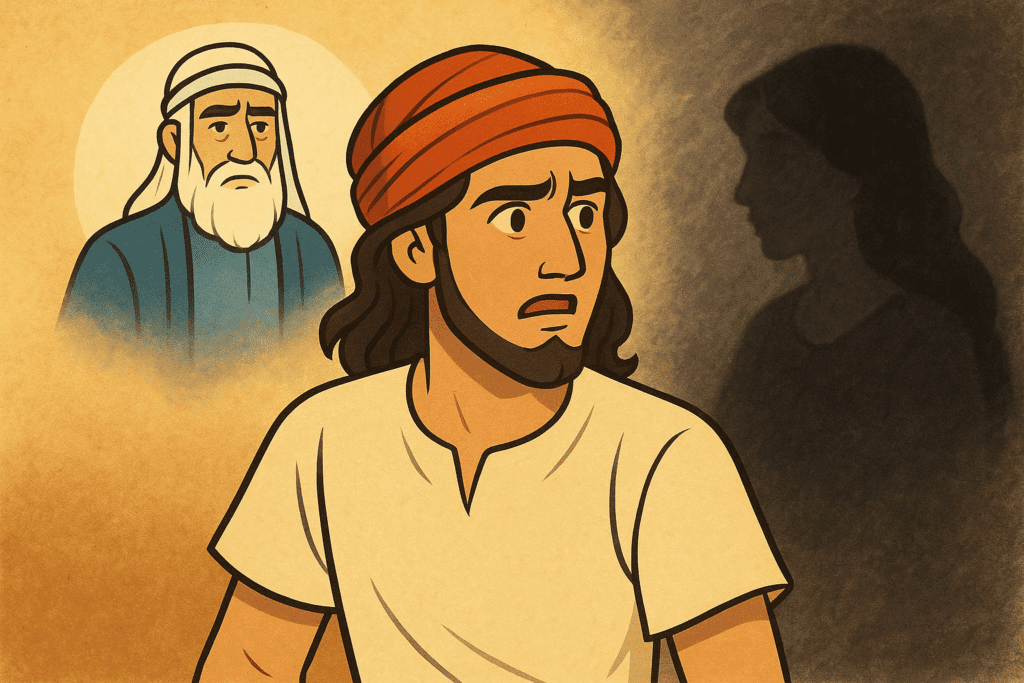

Chazal say that at that moment he saw the image of his father. Earlier in the parsha, the Torah tells us that Yaakov loved Yosef because he saw himself in him—they looked alike. In that moment, Yosef doesn’t just remember Yaakov. He sees who he could become. He looks at himself and sees his father looking back.

This teaches something very powerful: what children see is what they know.

Role models are not speeches. They are mirrors.

There’s another layer. Earlier in the parsha, when Yaakov is told that Yosef is dead, the Torah says “vayema’en lehitnachem”—Yaakov refuses to be comforted. One refusal echoes another. A father who refuses to give up on his son gives his son the strength to refuse when it matters most. Even subconsciously, that faith carries forward.

Then comes the final moment: Yosef leaves his beged behind.

A beged is clothing—the outer layer, not who we really are.

But beged, bagad, begida also means betrayal and deception.

Look at the letters ב–ג–ד.

They sit right next to each other in the aleph-bet. That represents a narrow vision—seeing only what’s directly in front of you. The moment. The pleasure. The surface.

That’s exactly the test Yosef faced.

But Torah truth is emet.

א–מ–ת—the first, middle, and last letters of the aleph-bet.

Truth means seeing the whole picture: where I come from, where I am, and where this leads.

Yosef chooses emet over beged.

He walks away from the clothing, from the superficial moment, from the immediate pleasure—and holds onto who he truly is, even at great cost.

That is not just self-control.

That is clarity of vision.

That is kingship.

And now we can understand the word vayema’en even more deeply.

In halacha, mi’un appears in a very different context: a ketana, a young girl who was married off while still a minor. When she grows older and reaches awareness, she can say one simple sentence: “Eini rotza”—I don’t want. And with that clarity, the marriage ends.

Mi’un is not rebellion.

It’s not drama.

It’s not struggle.

It’s maturity.

It’s the language of someone who says: I’ve grown. This no longer fits who I am.

That’s why mi’un appears here too.

Yaakov refuses to be comforted—because a father knows when a story isn’t over.

Yosef refuses—not because he’s fighting desire, but because he’s outgrown it.

Yosef doesn’t say, I want this but I mustn’t.

He says, This is beneath me. This is not who I am becoming.

That’s vayema’en.

And that is what our children learn—not from what we say, but from what we refuse to give up on… and from what we have the courage to outgrow.